The humble philanthropist Florence Waite (1861-1946) left the bulk of her estate worth more than $7.5 million in today’s dollars to be carefully distributed among more than 20 hometown organizations, many of which she had helped for decades. She anonymously gifted the copper sign above the New Bedford Whaling Museum’s original entrance on North Water Street to attribute the name of the governing body of the Museum, the Old Dartmouth Historical Society.

Citation: “Sign reading ‘Old Dartmouth Historical Society,’ North Water Street,” Silver gelatin print, New Bedford Whaling Museum Photograph Archive, 2000.100.3700

My interest in Florence Waite (1861-1946) began before I knew her name. It started with a sign from above, not a supernatural sign, but a metal one mounted high above the Whaling Museum’s original 1906 entrance on North Water Street. For years, I paused along the cobbled lane to admire the ancient copper sign fastened to the ornate brownstone. It is a vestige of a bygone age, but placed there not so long ago, as its whimsical design reveals that its creator was looking back, intending to convey an air of romantic nostalgia like that of a seagoing adventure novel. It is an odd invention, an oversized double-fluke harpoon from which is suspended the yardarm of a ship rigged with a billowing square sail from which projects heavy black lettering: OLD DARTMOUTH HISTORICAL SOCIETY. There seemed to be no trace of who placed it there or why. It was Florence’s sign.

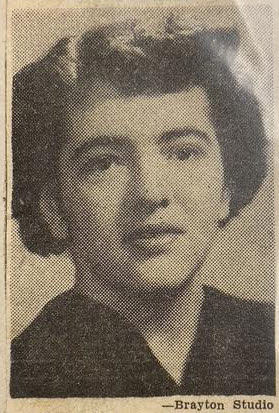

Except for her sign, only faint traces remain of the life and pursuits of Miss Waite. While on the surface this might not be surprising for a solitary woman born 155 years ago, it is unusual for a person so involved in her community that she left the bulk of her estate, worth more than $7.5 million in today’s dollars, to a multitude of organizations in her hometown. Why is her memory so obscure? The short answer is she may have wanted it that way. That she valued her privacy is evident (few photos have been found of her), and yet she was involved in many local organizations throughout her life, including the Old Dartmouth Historical Society. She was a founding member of this institution, which endeavors to remember her always.

The Waite family traced back to Thomas Wait (1601-1677), who came to America in 1634 via Boston, settling in Portsmouth, Rhode Island in 1638. He bought land in what is now Acushnet in 1661.

Second youngest of the five children of Benjamin Howard Waite (1824-1898) and Martha Jefferson Blodgett Waite (1829-1908), Florence was born in December 1861, a turbulent and grim time in a nation torn asunder by the Civil War. It was a bad time for the whaling industry, too. Ben Waite’s fortune, however, was not directly tied to the sea, though he did invest in several whaling voyages. In 1864, he purchased a stunning Italianate mansion at Cottage and Arnold Streets. Florence would call it home for the rest of her life.

A native of Tiverton, RI, Ben was born in 1824 to Peleg and Ruby (Howard) Waite. The family moved to New Bedford when he was a child and he was educated in the public school.

Florence’s three sisters all married, but none had surviving children. Florence’s elder sister, Clara Cornelia (1852-1934), married R. Manning Gibbs of Fall River, Massachusetts. Her younger sister, Daisy Mabel (1869-1942), married Phineas C. Hadley, of New Bedford in 1892. Florence never married and lived with her aging parents and their two servants.

A shrewd businessman, Ben invested in national corporations, textile mills and bought real estate throughout the city. B.H. Waite & Co. was a popular retailer of dry goods and carpeting. The Waite Building stood at 71 William Street, and housed several business tenants, including the fledgling New Bedford Telephone Company. As telephones became the norm, utility poles with multiple tiers of wires forested the city, and scores of them led to the Waite Building, then the local hub of a nascent telecommunications network.

Benjamin died in 1898 and was buried in the Waite family plot at Rural Cemetery beneath a massive monument located in the finest section (Albert Pinkham Ryder is buried nearby). Ben’s wife died in 1908.

Florence remained in the house and continued her involvement in the city’s charitable organizations. She served on the ODHS House Committee with Robert C. P. Coggeshall, superintendent of the city’s water works. Her most visible act came in 1916, a turning point for the ODHS. Another heiress, Miss Emily Howland Bourne (1835-1922), whose roots also ran deep in New Bedford, informed ODHS president William W. Crapo of her intention to build a grand museum edifice atop Johnny Cake Hill, to be dedicated to the memory of her father, whaling magnate Jonathan Bourne (1811-1889). She chose Henry Vaughn, a prominent church architect to design the building that would adjoin the ODHS museum on North Water Street.

Unlike Florence’s philanthropic pursuits, Emily’s project was everything but low-key. Not only would the new museum be constructed in an elegant Georgian Revival style, it would be purpose-built to receive Emily’s second and equally stunning gift, a half-scale model of her father’s favorite (and most profitable) whaling ship. Edgar B. Hammond would build the model. The press covered the progress as the towering ship model rose in the great hall.

The ODHS minutes of 1915 relate great anticipation and excitement. President Herbert W. Cushman exhorted the membership to follow Miss Bourne’s example. “The thoughtfulness and the purpose which has been back of the gift which Miss Emily H. Bourne is to give to us, must be an inspiration to all of us to do our part to carry on the good work.” Doubtless, Florence was listening. Though far smaller than Emily’s gift, Florence’s gift of the ODHS sign did not lack in symbolism.

The grand opening of the Jonathan Bourne Whaling Museum took place on 22 November 1916. It attracted hundreds of guests and throngs of onlookers along Johnny Cake Hill, its stately entrance facing the Seamen’s Bethel. Thereafter, the entrance on North Water Street became secondary. To address the situation, Florence collaborated with her neighbor, Howard S. Bowie (1875-1961), to create a sign that would make permanently visible the ODHS name, which was (and is) the governing body of the Museum.

Less than a week before Emily’s presentation of the Bourne Museum on the hill, Florence’s sign for the ODHS was installed unceremoniously at the original Water Street entrance, the sign’s harpoon pointing east towards the rising sun from the head of Centre Street, once a prominent thoroughfare of the whaling era. The press reported the sign was “given to the society by a woman member, whose identity has not been divulged.”

Florence died 7 July 1946. In her 84 years, she witnessed tremendous change in the city, from a whaling port to a post-WWII industrial powerhouse. In her Last Will and Testament, she revealed herself as a great philanthropist, carefully distributing her wealth to more than 20 hometown organizations, many of which she had helped for decades.

Four years after her death it was made public that Florence had given the sign and was an ODHS benefactor. Florence’s bequest enabled the ODHS to acquire abutting land on North Water Street. Fifty years later, it became the site of the Jacobs Family Gallery in 2000.

Arthur Motta

![[Florence W. Waite], 1921, Photograph, Courtesy of Katherine N. Gibbs Photograph of Florence W. Waite - a headshot of an older woman with short grey hair, wearing a dress and cardigan](https://historicwomensouthcoast.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Florence_W_Waite_1921_oval-533x533.jpg)