Writer, abolitionist and educator, Harriet Ann Jacobs (1813-1897) is the only African American woman known to have left writing documenting her enslavement. After her escape, she worked as a nursemaid for the family of Nathaniel Parker Willis and wife Cornelia Grinnell Willis, who would shelter her from recapture at the Grinnell home in New Bedford. Her book Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself is the most comprehensive antebellum autobiography by an African American woman.

Although millions of African American women were enslaved over 250 years in the United States, Harriet Ann Jacobs (1813-1897) is the only one known to have left writing that documents that enslavement. Born a slave in 1813, Harriet recorded the degradation of slavery, survived sexual oppression and escaped from a master who sought to possess her. Harriet is now known as the author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself (1861), the most important slave narrative by an African American woman. Jacobs is also important because of the role she played as a relief worker and educator among Black Civil War refugees in Alexandria, Virginia and Savannah, Georgia. Throughout most of the twentieth century, Jacobs’ autobiography was thought to be a novel by a White writer, and her relief work was unknown. With the 1987 publication of an annotated edition of her book, however, Jacobs became established as the author of the most comprehensive antebellum autobiography by an African American woman.

Harriet Ann Jacobs, writer, abolitionist and reformer, was born a slave in Edenton, North Carolina in 1813. She was the daughter of two slaves owned by different masters. The story of her life, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself, was published under the pseudonym Linda Brent in 1861. It helped build Northern sentiment for emancipation during the Civil War and was probably the only slave narrative to deal with sexual oppression as well as oppression of race and condition.

During her childhood in Edenton, young Harriet lived with her mother as part of a close-knit family. Her father was a skilled carpenter who was loaned out for hire. Her maternal grandmother, Molly Horniblow, was emancipated by her mistress during the American Revolution, sold back into slavery as a prize of war, and was re-emancipated in 1828. When Harriet’s mother died in 1819, the six-year-old girl was taken into the home of her mistress, Margaret Horniblow, who taught her how to read and write. Harriet was very fond of Miss Horniblow and expected to be emancipated. Instead, when Miss Horniblow died in 1825, she willed Harriet to her three-year-old niece, Mary Matilda Norcom. Within two years of moving into the Norcom home, Harriet found herself the object of Dr. Norcom’s unwanted sexual advances and Mrs. Norcom’s vindictive jealousy. Through very intelligent and ingenious techniques, Harriet continually evaded Dr. Norcom’s sexual advances toward her. He refused to allow her to marry. However, Samuel Sawyer, a lawyer in the town, seduced Harriet when she was 16 years old and she had two children by him.

Harriet’s son Joseph was born in 1829 and her daughter Louisa Matilda was born in 1833. In retaliation, Dr. Norcom sent Harriet to one of his plantations to be broken in as a field hand. Before her children could be sent to join her, Harriet ran away and went into hiding at her grandmother Molly Horniblow’s house where she hid for seven years in a space under the front porch roof. Between 1835 and 1842, Harriet Jacobs wrote to Dr. Norcom telling him that she had escaped to the North in an effort to get him to sell her children. She thought that if he believed she had escaped to freedom and that she would not be returning that he would sell her children, but that never happened.

In 1842, Harriet escaped from Edenton by boat, traveling eventually to New York, where she went to work as a nursemaid for the family of Nathaniel Parker Willis and his second wife Cornelia Grinnell Willis. For the next few years, she traveled between New York, Boston, and New Bedford eventually reuniting with her children. During this period, she became active in a circle of anti-slavery feminists and met Amy Post, who, along with Cornelia Willis, would encourage her to write the story of her life. There are several recorded instances of Harriet being sent to New Bedford to stay with the Grinnell family on County Street in order to shelter her from the Norcom family, who sought to kidnap and re-enslave her. Eventually, in order to subvert the continued efforts of Harriet’s former owners to re-enslave her, Cornelia Willis bought Harriet’s freedom in 1852. The next year Harriet began work on Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Horace Greeley published some of the autobiography in the New York Tribune. Her account of how she had been sexually abused shocked the American public; however, when her autobiography was completed, she found it difficult to get it published. Harriet finally purchased the plates of her book and had it published by a Boston printer “for the author” in 1861.

Through the war years, Harriet lived in Washington, D.C., assisting contrabands, nursing Black troops and teaching. New Bedford women abolitionists supported Harriet’s actions by sending much needed teaching materials and supplies south. After the war, she and her daughter did relief work in Savannah and Edenton. In 1868, they traveled to London to raise funds for an orphanage and home for the aged in Savannah. The year before her death in 1897, she was actively involved in organizing meetings of the National Association of Colored Women in Washington, D. C. She is buried in the Mt. Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, MA.

Reprinted with permission from Bridgewater State University. “Harriet Ann Jacobs.” Massachusetts Hall of Black

Achievement, Item 10, Bridgewater State University, 2002, http://vc.bridgew.edu/hoba/10.

edited by Lee Blake

Addendum: One of Harriet Jacobs’ relatives is Alberta Mae Knox, the first Black graduate of New Bedford High School, master teacher, and president of the New Bedford branch of the NAACP.

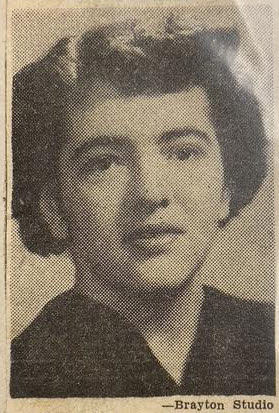

![[Harriet Jacobs], 1894, Photograph, The Harriet Jacobs Papers Photo of Harriet Jacobs](https://historicwomensouthcoast.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Harriet-Jacobs-287x287.jpg)