Known as both “The Witch of Wall Street” and “The Queen of Wall Street,” Henrietta “Hetty” Howland Robinson Green (1834-1916) was the richest woman in the world, her worth estimated at over $100 million, the equivalent of about $2.5 billion today, at her death in 1916. As a model of groundbreaking financial intelligence and independence, she was called “Mrs. Hetty Green” while her husband was known as the husband of Hetty Green.

Henrietta “Hetty” Howland Robinson Green (1834-1916), the richest woman in the world at the time of her death, has been known as both “The Witch of Wall Street” and “The Queen of Wall Street” for her unconventional ways amid extraordinary financial success. Her mother, Abby Slocum Howland, was the daughter of wealthy whaling fleet owner Gideon Howland. Her father, Edward Mott Robinson, was Gideon’s business partner. Edward Robinson married Abby Howland with the intention of having a son to inherit and increase his wealth. On November 21, 1834, Abby gave birth in New Bedford to their firstborn, a daughter they named Henrietta. Abby soon had a son who died a few weeks after birth. Edward, enraged that there was no son for him to mentor, threw himself into his work; Abby, terrified of her husband and depressed over the loss, went to bed. By the time Hetty was two years old, her parents had sent her to live with her grandfather Gideon and his older daughter Sylvia Ann Howland, Abby’s sickly sister.

During Hetty’s early childhood, Aunt Sylvia attempted to become Hetty’s surrogate mother. But Aunt Sylvia, unhealthy with spinal problems since birth, had no patience for Hetty’s childhood tantrums. To assist Gideon and Sylvia, Hetty’s mother sent a servant to take care of Hetty and a tutor to educate her. By the age of six, as Hetty excelled at math and reading, she read the daily newspapers, including the financial reports, to her grandfather and father. At the age of eight, Hetty opened up a bank account with saved nickels from allowances and rewards for good behavior. Hetty would soon accompany her grandfather and father on the waterfront as they ran their successful whaling business, Isaac Howland Jr. and Company. She paid close attention to her father on the docks as he inspected ships and negotiated with captains and merchants. As Hetty gained her father’s approval, he taught her how to read the books at the counting house and how to trade stock at the brokerage. Upon her grandfather Gideon’s death, Hetty’s father became the principal partner of the family business and controlled his wife Abby’s share of the inheritance. Hetty learned the business by listening to her father as he increased their assets through careful management and wise investments.

Hetty’s formal education began at the age of 10 when her parents sent her to a strict Quaker boarding school in Sandwich. At the age of 15, Hetty attended a summer session at Friends Academy, followed by three years at a Boston finishing school, where debutantes were taught academics as well as the social etiquette of teas, dinners, and dances. During school breaks in New Bedford, Hetty had rooms at both Aunt Sylvia’s home on Eighth Street and her father’s house on Second Street. During weekends and summers, Hetty and the family often took a two-hour carriage ride to the family’s summer home at Round Hill in Dartmouth. These idyllic summers spent with family would not last forever, as tension steadily grew between Hetty and Aunt Sylvia, the other beneficiary of Gideon’s fortune.

While Hetty worked for her father and kept track of her spending, the more extravagant Sylvia had little patience for Hetty’s shabby wardrobe and occasional outbursts. Hetty’s father reassured Hetty that she alone would inherit her parents’ and her aunt’s wealth as the sole living heir to the family fortune. Hetty understood this promise to include her complete control of the inheritance, but her father had other plans. When her mother Abby died in 1860 without a will, her entire estate of more than $100,000 went to Abby’s father, who promised to leave the money to Hetty upon his own death. Hetty was able to keep only a house worth $8,000. Hetty accepted the outcome and moved to New York with her father, who wisely transitioned his business from faltering whale oil to shipping cargo. She worked closely with her father in building a portfolio of stocks, bonds and real estate. Hetty also socialized, and at an 1860 ball in honor of the visiting Prince of Wales in New York City, Hetty introduced herself as the “Princess of Whales,” a playful reference to her connection to New Bedford’s whaling industry. During her years in New York, Hetty returned regularly to New Bedford and Round Hill, often to argue with Aunt Sylvia over the terms of her will.

Hetty’s disappointment over her inheritance would continue. When her father died in 1865, he left Hetty about $900,000 directly and about $5 million in trust. Hetty was devastated to realize that even though she had been her father’s attentive business student, her father did not trust her with the bulk of the family fortune. Two weeks later, Aunt Sylvia died as the richest woman in New Bedford with over $2 million. A will was produced that gave $1 million to charities and $1 million in trust to Hetty as investments to be managed by Sylvia’s physician. Hetty produced a letter that claimed that she was the lawful heir, but the defendants claimed that the letter was forged. Years later, both sides reached a compromise.

Despite her family’s unwillingness to give her complete control over her inheritance, Hetty developed an intelligent investment strategy for the wealth that she could manage directly. She began by contrary investing, buying when stock was low and selling when stock was high. She researched, questioned and read constantly before deciding what to invest in and what to avoid. She invested in railroads, real estate and government bonds. By 1885, she increased her fortune to $26 million. At her death in 1916, Hetty was the richest woman in the world, with her worth estimated at over $100 million, the equivalent of about $2.5 billion today.

On July 11, 1867, Hetty Howland Robinson married Edward Henry Green, a wealthy Vermont businessman who was a millionaire by age 44. Hetty had Edward sign a pre-nuptial agreement, a wise decision given his tendencies for risky speculation and extravagance. For seven years, the Greens lived in London, where they had two children, son Edward “Ned” followed by daughter Sylvia. Soon after their return to America, the Greens relocated to Edward’s hometown of Bellows Falls, Vermont. Hetty repeatedly rescued Edward financially from increasing debt. To get away from the troubled marriage, Hetty and the children spent six weeks in New Bedford and Round Hill in the summer of 1882. In 1885, when Cisco Bank refused to transfer her $550,000 to Chemical National Bank, she learned that Edward planned to use her money to cover his losses without her permission. Although she did not divorce him, their marriage never recovered from this ultimate betrayal that squandered some of her wealth.

Hetty returned to New York with the children and set up an office at Chemical National Bank, where she thoroughly analyzed the worth of companies before investing. Newspapers referred to her as the “Witch of Wall Street” for her black clothing and stories of cold frugality, including her refusal of medical treatment for her son which led to a leg amputation. Yet, she reportedly donated to Barnard College, the Nurses Home, a group of New York pediatricians, and others. Papers also called her the “Queen of Wall Street” as she ruled the male-dominated world of American finance. At the Chemical Bank, on a daily basis, the queen would hold court as men sought her guidance.

In a series of interviews, Hetty offered advice for women on business. “A girl should be brought up as to be able to make her own living, whether or not she’s going to inherit a fortune,” Hetty insisted. She believed that women should learn about bank accounts, mortgages, bonds and how interest works. She maintained that married women could also be businesswomen. As a model of groundbreaking financial intelligence and independence, she was called “Mrs. Hetty Green” while her husband was known as the husband of Hetty Green.

Hetty died on July 3, 1916, with her children by her side in New York City. Aside from $1 million given to Gideon Howland’s descendants and $25,000 left to friends, the rest of her $100 million estate went to her children. For Hetty, her most valuable gifts were the jobs that her wealth created through her investments in this country. She is buried in Bellows Falls, Vermont.

Ann O’Leary, Emily Bourne Research Fellow

Information from

-

“Henrietta ‘Hetty’ Howland Robinson Green.” National Women’s History Museum, https://www.nwhm.org/education-resources/biography/biographies/henrietta-howland-robinson-green/.

-

Wallach, Janet. The Richest Woman in America: Hetty Green in the Gilded Age. Doubleday, 2012.

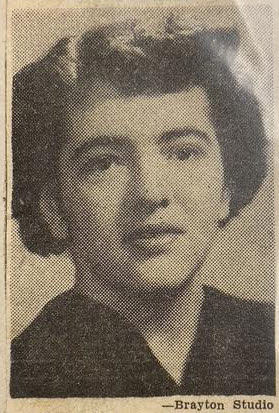

![[Hetty Green Portrait], by Fred W. Palmer, c.1905, Negative, Glass, Dry Plate --Copy Negative, Courtesy of New Bedford Whaling Museum, 2000.100.80.260 Profile photo of Hetty Green at 18 years old](https://historicwomensouthcoast.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Hetty-Green-440x440.jpg)