Abolitionist, women’s rights advocate, and women’s club founder, Cornelia Grinnell Willis (1825-1904) advocated for and provided funding for Harriet Jacobs’ freedom, and it was under her roof that Harriet secretly wrote the historically significant narrative, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Cornelia devoted her life to promoting opportunity and the right to education for all women.

As a steadfast caretaker, women’s rights advocate, founding member of the “first woman’s club” in the United States, and abolitionist, Cornelia Grinnell (1825-1904) was a force to be reckoned with and had a decidedly positive effect on the lives of many individuals and families throughout her adult life.

Following the death of her parents, Elizabeth Tallman Russell and Cornelius Grinnell, Jr., Cornelia became the ward and only child of her father’s brother, Joseph Grinnell, and his wife, Sarah Russell Grinnell. In 1836, Joseph Grinnell, having achieved fame as an abolitionist and success in his many business ventures in New York and Massachusetts, built his mansion on County Street in New Bedford. It has been recorded that on December 25, 1844, Cornelia hosted a party at the mansion, complete with gifts for the guests and a Christmas tree lit by candles, perhaps the earliest such celebration in New Bedford.

Cornelia was schooled in New Bedford and travelled to Europe, where her adoptive father commissioned a likeness of her by the preeminent American sculptor Horatio Greenough, a Boston native who resided in Florence, Italy. In 1843, the Grinnell family moved to Washington D.C., where Joseph Grinnell served as a member of the House of Representatives. During that time, Cornelia met her future husband, Nathaniel Parker Willis, a celebrated poet, journalist and social commentator who was a widower with a young daughter, Imogene Willis. Prior to his first wife’s death, Mr. Willis hired Harriet Jacobs to be Imogene’s nursemaid, unaware that Harriet had escaped enslavement in North Carolina. Cornelia and Nathaniel were married in 1846, giving Imogene Willis a new stepmother and Harriet Jacobs further employment. Cornelia gave birth to five children, losing the youngest, a daughter, at birth.

While living in the Willis home, Harriet Jacobs secretly wrote Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, one of the few surviving slave narratives written by a woman. It was through this autobiography that she managed to share the story of unwanted advances from her slave owner, hiding in her grandmother’s attic crawl-space for seven years and her eventual escape. It was through the Underground Railroad, a network of marine transport, homes, and conductors, that Harriet had made her way to New York and freedom.

In 1852, her “owner’s” arrival was published in the newspaper. Cornelia assured Harriet’s safety by hiding her first in the home of a friend in New York and then sending her to New Bedford to be sheltered in the Grinnell Mansion. Later, Cornelia managed to “purchase” Harriet’s freedom, thereby ending the author’s fear of recapture. Cornelia and Harriet often resided in the same household in New York, New Bedford (while summering with the Grinnell family), Cambridge (MA), and Washington, D.C. Cornelia started a school in 1863 for young women at her New York home, the Willis estate of Idlewild. She was forced, however, to give it up in 1866, when her husband became too ill to continue living in New York.

Cornelia wrote a column in the New York Ledger about the role of women as advocates and hostesses. She modeled her philosophy by becoming one of the original founders of the first women’s clubs in the United States, New England Women’s Club, in Boston in 1868.

After Nathaniel Willis’s death, Cornelia traveled with her children throughout Europe and saw them through their education. The youngest child, Bailey Willis, graduated from Harvard College in 1870. During this time, Cornelia lived in Harriet Jacobs’ popular boarding house in Cambridge. Cornelia later lived in Washington, D.C., where she and two of her daughters nursed and advocated for Harriet Jacobs until her death in 1897. Cornelia died in 1904 in Washington, D.C. She is buried in New Bedford’s Oak Grove Cemetery.

Ivy S. MacMahon

Information from

-

Emery, William. M. The Howland Heirs. E. Anthony & Sons, 1919.

-

Medeiros, Peggi. “When Christmas Came to New Bedford.” SouthCoast Today, 21 Dec. 2014, http://www.southcoasttoday.com/article/20141221/NEWS/141229914.

-

Pease, Zephaniah W., editor. History of New Bedford. The Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1918.

-

Yellin, Jean Fagan, et al., editors. The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers. U of North Carolina P, 2008.

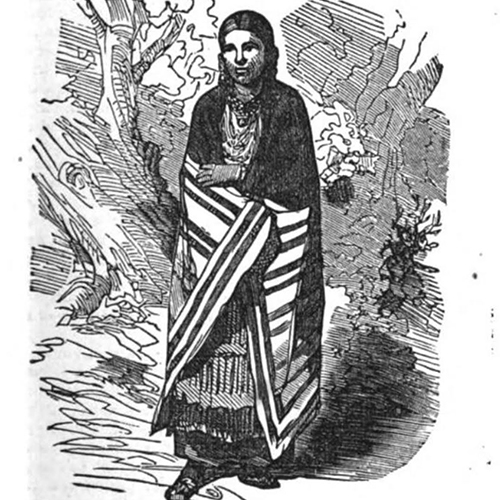

![[Cornelia Grinnell], c.19th century, Photograph, Courtesy of Joint Free Public Library of Morristown and Morris Township Photograph of Cornelia Grinnell - older woman in a dark dress sitting in a rocking chair inside a home, possibly a living room.](https://historicwomensouthcoast.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Cornelia-Grinnell-e1526497107419-496x496.jpg)