Annie Holmes Ricketson (1841-?) accompanied her husband on at least three whaling voyages, chronicled in journal entries filled with details about life as the lone woman aboard ship. Annie lost her newborn daughter in Faial, Azores, as well as her husband on a return trip home. Annie and other whaling wives endured rough seas, terrible tragedies, painful homesickness, and limited companionship of other women.

On May 2, 1871, Annie Holmes Ricketson (1841-?) left New Bedford on the whaleship A.R. Tucker with her husband, Captain Daniel L. Ricketson, for a voyage to the Indian Ocean and South Atlantic that would last over three years. Thirty years old and six months pregnant, Annie would experience both great joy and deep sorrow on this voyage, chronicled in a journal filled with details about life as the lone woman aboard the ship. Annie chose to sail with him on at least three voyages, leaving her family for years at a time, as an alternative to long separations from her husband.

Citation: Church, Albert Cook, “A.R. Tucker-Drying sails-stern view,” Negative, glass, dry plate, New Bedford Whaling Museum, 2000.100.86.121

“I think I am getting to be quite a sailor for I have not been sick at all,” she writes on August 25, 1871, as huge waves washed across deck. The next day, the A.R. Tucker arrived at Faial, Azores so that Annie could have her baby. On August 29, Annie gave birth to a daughter and all seemed well. But on August 31, her infant died and Annie mourns, “This morning I woke as happy as ever, little thinking that before night I should be in sorrow. My little baby was sick all day. It would cry out with pain all day and towards night I noticed that Its cry was weaker . . . They took it away from me and put it in the next room . . . But o how hard it was to give that little thing up!” Annie would continue to express her grief in the weeks that followed. On September 1, after the baby’s burial on Faial, Annie continues, “They layed it in a pretty green spot Daniel says with trees round it that shade it. Now my little one is an angel with the angels in Heaven. It is much better off than it would be here in this wicked world of ours.” Before the end of that September, Mrs. Taber, another captain’s wife, would also give birth on Faial to a daughter who would die within days. In her journal, Annie expresses sadness over Mrs. Taber’s loss and is reminded of her own baby’s passing. On Faial, through celebration and sadness, Annie appreciates the company and support provided by other women, including Mrs. Graham who assisted at the birth and Miss Beaver who helped with the burial.

Annie’s journal entries from two voyages aboard the schooner Pedro Varela describe the harshness of whaling, harrowing illness and yet another tragedy. In an 1881 voyage, Annie tells of the heat, grease, smoke and “very bad” smell of whaling. To break up the grim monotony of this voyage, Annie spent time sewing a “Job’s Trouble Quilt,” a pattern inspired by the Old Testament story of Job, who never lost faith amidst suffering. She notes that the men made sketches stained with lamp black on clean whale teeth, scrimshaw, to fill their down time. In April 1885, after surgery on Barbados to alleviate an infection, Daniel suffered a breakdown, with bouts of extreme violence that required Annie and others to restrain him, as reported in her tear-stained journal. After a slow recovery and a brief return home, Annie and Daniel set out on what would be their final voyage. In September 1886, after a year at sea, the Pedro Varela picked up three sick men and the disease spread. Annie was sick and recovered, but Daniel worsened by the time they arrived at St. Michael, Azores. Annie was unable to get a doctor with the schooner placed under quarantine and a boat headed for America refused them passage. On October 10, 1886, Daniel died at sea on the return trip home of the Pedro Varela.

Annie was born in Fall River on July 14, 1841 and married Daniel L. Ricketson in 1857 at the age of 16. At age 26, four years before joining her husband on the A.R. Tucker, her first baby died at birth. Annie lost her second baby and her husband while on voyages far from home. Although she remarried twice, little is known about her life back on shore.

Annie and other whaling wives broke the stereotype of women as staying home and passively waiting for their husbands to return. While at sea, these women endured rough seas, strange lands, terrible tragedies, painful homesickness, and limited companionship of other women. Annie’s journals show her amazing ability to accept and adapt to circumstances with courage and grace.

Ann O’Leary, Emily Bourne Research Fellow

Information from

-

Druett, Joan. Petticoat Whalers: Whaling Wives at Sea 1820-1920. University Press of New England, 2001.

-

Ricketson, Annie Holmes. “Annie Holmes Ricketson.” A Day at a Time: The Diary Literature of American Women from 1764 to the Present, edited by Margo Culley, The Feminist Press at CUNY, 1985, pp. 143-148.

-

Ricketson, Annie Holmes. The Journal of Annie Holmes Ricketson on the Whaleship A.R. Tucker, 1871-1874. Old Dartmouth Historical Society, 1958.

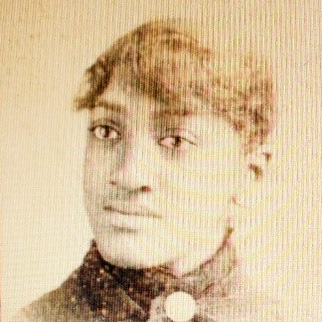

![J. C. Knowles, "[Annie Holmes Ricketson]," Carte-de-visite, New Bedford Whaling Museum, 2000.100.2126 Photograph of bust of woman in brown towns. Woman is wearing earrings and a lace collar tied with a brooch.](https://historicwomensouthcoast.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Annie-Ricketson-e1648139020371-613x613.jpg)