New Bedford’s Ellen Kempton (1840-1865) lost her life while in South Carolina to educate and assist formerly enslaved people. She demonstrated tenacity of faith and commitment to make the everyday life of a struggling community purposeful and educated. As a young social reformer and teacher, Ellen left home and family to dedicate herself to the freed individuals and families on a ravaged southern island.

The life of Ellen Stanton Kempton (1840-1865), one of New Bedford’s most promising and courageous young citizens, ended tragically at the age of 25 in a boating accident in South Carolina. Committed to the ideals of religious and social reform, Ellen and Elmira Stanton (from Lowell, MA) had gone to South Carolina on a mission to teach formerly enslaved children on behalf of the Boston Freedmen Association.

Ellen Kempton was born on June 17, 1840, in New Bedford, Massachusetts. She was the third child of Silas Swift Kempton and his second wife, Lydia Davis Smith. A dominant Quaker influence made New Bedford a stronghold of abolitionist thinking. In Ellen’s years of growing up in the city, she would have been familiar with New Bedford as a “safe harbor” for fugitives from slavery. At that time, New Bedford had attracted one of the largest Massachusetts populations of people of color, all seeking a place in which they might become truly free and employed.

Ellen taught for the New Bedford Public Schools and in 1865 was sent by the New England Freedmen’s Society and New Bedford’s Aid Society to South Carolina to assist people of color resettled on South Carolina’s Edisto Island. Ellen kept a journal of her trip starting on April 24, 1865. Her last entry was in November of 1865. Her journal tells of the day-to-day hurdles and deprivations. The teachers, often young women from the North, had not been adequately advised on what they should bring along with them. The Freedmen’s Bureau was not able to predict where or how the teachers might be housed in South Carolina, and the two young women from Massachusetts found themselves on Edisto Island, a place of abandoned plantations. Owners had burned many of their crops and fled during the Civil War. The two teachers were shown several possible locations for their housing and their school. They chose the Whaley Plantation, which had been stripped of all its furniture and amenities. They only had their clothing and a few personal effects, no cooking or cleaning equipment, and only cloth-sacks to pack whatever filling they might gather from the out-of-doors to create a bed.

Citation: Kempton, Ellen, “[Ellen Kempton’s Journal],” 1865, Document, New Bedford Whaling Museum Grimshaw Gudewicz Reading Room and Archives, Collection Mss 64, Series K, Sub-series 8

The flowing script of her diary takes the reader along with her as she attempts to improve the lives of islanders who were being guarded by Freedmen’s Bureau troops. Heat, insect infestation, lack of transportation and needs of the poor inhabitants taxed their every strength. The teachers did not lack students, as those who were not old enough to work the fields were curious and surprised to find such gifts as teaching and kindness. Both New Bedford’s and Springfield’s Freedman’s Aid Societies sent money, clothing, food items and books.

The Kempton Family sent their daughter, a teacher, on a mission. They had no idea that they would never see her again. On Christmas Day, Ellen, Elmira Stanton and friend/school superintendent/attorney James P. Blake set out on the St. Pierre Creek to visit friends. Their boat capsized on the return trip, and all three drowned. Ellen and her two companions were buried in the Cemetery of the Edisto Island Congregational Church.

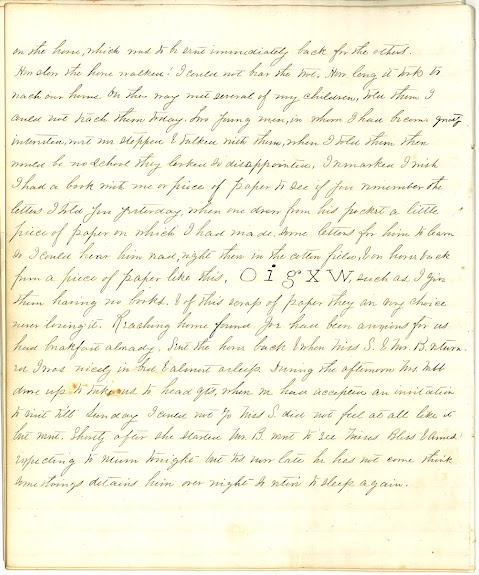

Ellen Kempton’s younger sister, Anna Kempton, became the caretaker of Ellen’s journal, which was given to the New Bedford Whaling Museum. The diary is covered in reddish brown pebbled leather with gold letters reading “Ellen S. Stanton” engraved on the front cover.

Ivy S. MacMahon

Information from

-

Butchart, Ronald E. Schooling the Freed People. U of North Carolina P, 2010.

-

“Extracts from Teachers Letters from Edisto Island.” Collection of African American Newspapers, 1 Jan. 1866. (Elmira B. Stanton, Ellen S. Kempton and Harriet Jacobs).

-

Grover, Kathryn. The Fugitive’s Gibraltar: Escaping Slaves and Abolitionism in New Bedford, Massachuetts. U of Massachusetts P, 2001.

-

Spencer, Charles. Edisto Island 1861 to 2006: Ruin, Recovery and Rebirth. The History Press, 2008.

![[Ellen Kempton], c. 19th century, carte-de-visite, Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society Photograph of Ellen Kempton - a woman with dark hair pulled back and a dark dress. She has one arm resting on a table.](https://historicwomensouthcoast.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Ellen-Kempton-1-384x384.jpg)