A color theory pioneer, artist, collector and philanthropist, Emily Noyes Vanderpoel (1842-1939) wrote the 1902 book Color Problems: A Practical Manual for the Lay Student of Color, a 400-page text that analyzes color proportions of objects to quantify the effect of color on the imagination. In 1893 she won a Bronze Medal at the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition and some years later, one of her paintings was displayed at the National Art Museum in Washington, DC.

A color theory pioneer, artist, collector and philanthropist, Emily Noyes Vanderpoel (1842-1939) was working at the beginning of the 20th century. With her view of color theory, she appears to stumble on minimalist movement, years before its popularity in the 21st century.

Emily Noyes was born in New York City to William Curtis Noyes and Julia Tallmadge Noyes on June 21, 1842. Her family was affluent and had deep roots in the country’s history. Emily’s maternal great grandfather, Benjamin Tallmadge, was George Washington’s “Spymaster” during the Revolutionary War. Educated in New York City private schools, she never received a formal art education, but later studied under Robert Swain Gifford and William Sartain, who taught at Cooper Union and the Arts Student League. Throughout her life, she enjoyed a modest reputation as a watercolorist and also painted in oil. She exhibited her works at the New York Watercolor Club where she served a term as vice president. The Club was formed by a group of artists in response to the American Watercolor Society’s refusal to accept women as members. She remained a lifelong advocate for women’s rights.

On May 22,1865 she married John Aaron Vanderpoel with whom she had a son, John Arent Vanderpoel. Tragically, her husband died at the age of 23, prior to her giving birth. She never remarried.

In 1893 she won a Bronze Medal at the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition and some years later, her painting Ypres, a memorial to the town in West Belgium destroyed during World War I, was displayed at the National Art Museum in Washington, DC. It is now lost.

As a woman of means and a head of her household, she had the freedom to pursue many passions. She wintered in New York City and summered in Litchfield, CT where she bought her great grandfather’s Georgian home. She served as the first curator of the Litchfield Historical Society and wrote a two-volume history of a Litchfield girl’s school founded by her great grandmother Mary Floyd Tallmadge. Her book American Lace and Lace-Makers is dedicated to Robert Swain Gifford, “A real Artist, A wise Teacher, A true Friend.” In 1899, she organized a chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, which was named for her great grandmother.

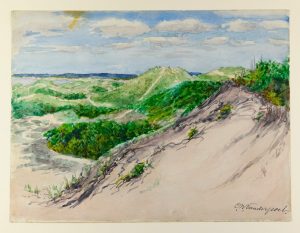

From 1919 to 1921 she maintained a summer residence on Barney’s Joy Road in South Dartmouth, MA. Five watercolors and three oil paintings of the area are owned by the Old Dartmouth Historical Society-New Bedford Whaling Museum.

At age 59, she created what is considered her biggest achievement, a book titled Color Problems: A Practical Manual for the Lay Student of Color. The book is dedicated to her father and was published in 1902. It was written primarily for non-artists, such as dressmakers, florists and decorators, occupations that were often held by women during the Victorian era. “Women,” Emily quips, “notice color more than do men.” The 400-page text includes 117 color plates that analyze the color proportions of actual objects. Many of the objects she used were part of her personal collection of exotic artifacts, such as Assyrian tiles, Persian carpets and mummy cloths. Her process for creating the plates is unclear.

Historian and science blogger John Ptak notes that Vanderpoel “sought not so much to analyze the components of color itself, but rather to quantify the overall interpretative effect of color on the imagination.” Vanderpoel reveals herself to be well versed in color theories that proliferated throughout the 19th century, due in part to scientific advances that led to the development of new pigments. She frequently refers to major names in the field, among them Michel-Eugene Chevreul, whose ground breaking 1839 book explored how adjacent colors influence one another; James Clerk Maxwell, who uses spinning color discs to show how people perceive mixtures of color; and Ogden Rood, who, among his other contributions, suggested that colors differ from one another due to variations in purity, hue, and luminosity. These men were scientists, and like them, Vanderpoel was interested in the technical aspects of color perception.

“Color,” Vanderpoel wrote, “is the music of light. Just as sound brings little pleasure until it’s woven into music.” Color Problems was reissued in 2018.

Emily died February 20th, 1939 at the age of 96 and is buried in East Cemetery in Litchfield, Connecticut.

Janice Linehan

Five of Emily Noyes Vanderpoel’s paintings are on display at New Bedford Whaling Museum as a part of the Re/Framing the View: Nineteenth-century American Landscapes exhibition through May 14, 2023.

Information from

- Blasdale, Mary Jean. Artists of New Bedford: A Biographical Dictionary. New Bedford Whaling Museum, The Old Dartmouth Historical Society, 1990.

- [Emily Noyes Vanderpoel] c. 1920, Collection of the Litchfield Historical Society, Litchfield, Connecticut, https://ledger.litchfieldhistoricalsociety.org/ledger/materials/292.

- “Emily Noyes Vanderpoel.” The Ledger, 2010, https://ledger.litchfieldhistoricalsociety.org/ledger/students/7173.

- “Emily Noyes Vanderpoel.” Sacred Bones Records, 2022,

- https://www.sacredbonesrecords.com/collections/emily-noyes-vanderpoel.

- “Emily Vanderpoel Artist and Author.” The New York Times Obituaries, 21 Feb. 1939.

- “For the Love of Beauty: The New England Aesthetic Style in Fine and Decorative Arts 1870-1920.” New Bedford Whaling Museum, https://educators.whalingmuseum.org/uploads/1/2/6/1/126158959/for_the_love_of_beauty_-_docent_notes_1.pdf.

- Grovier, Kelly. “The Women Who Redefined Color.” BBC Culture, 12 Apr. 2022, https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20220401-the-women-who-redefined-colour.

- Jow, Tiffany. “This Forgotten Female Artist Taught Us Everything We Know About Color.” Surface, 18 July 2018, https://www.surfacemag.com/articles/emily-noyes-vanderpoel-color-problems-book/.

- Katz, Brigit. “Revisiting Emily Vanderpoel’s Color Theory Book 117 Years After Its First Release.” Hyperallergic, 5 Nov. 2018, https://hyperallergic.com/467406/revisiting-emily-vanderpoels-color-theory-book-117-years-after-its-first-release/.

- Lasky, Julie. “New Life for a 1902 Manual about Color.” The New York Times, 4 Oct. 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/04/style/new-life-for-a-1902-manual-about-color.html.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Emily Noyes Vanderpoel.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 12 Aug. 2022.

![Emily Noyes Vanderpoel [Emily Noyes Vanderpoel in kimono], 1920, Collection of the Litchfield Historical Society, Litchfield, Connecticut A black and white photograph of Emily Noyes Vanderpoel standing by a fireplace wearing a kimono](https://historicwomensouthcoast.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Emily-Noyes-Vanderpoel-Kimono-e1671647203733-221x221.jpg)